Our mini-bus pulled over on the side of a viewpoint, and we hopped out of the vehicle carrying a camera in one hand and a bottle of beer in the other. Running parallel to the parking lot was a lane of fastidiously arranged tables, champagne glasses and all. Waiters were on a watch, checking if everything was as it should be. Such a beautiful setup.

If only they were ours.

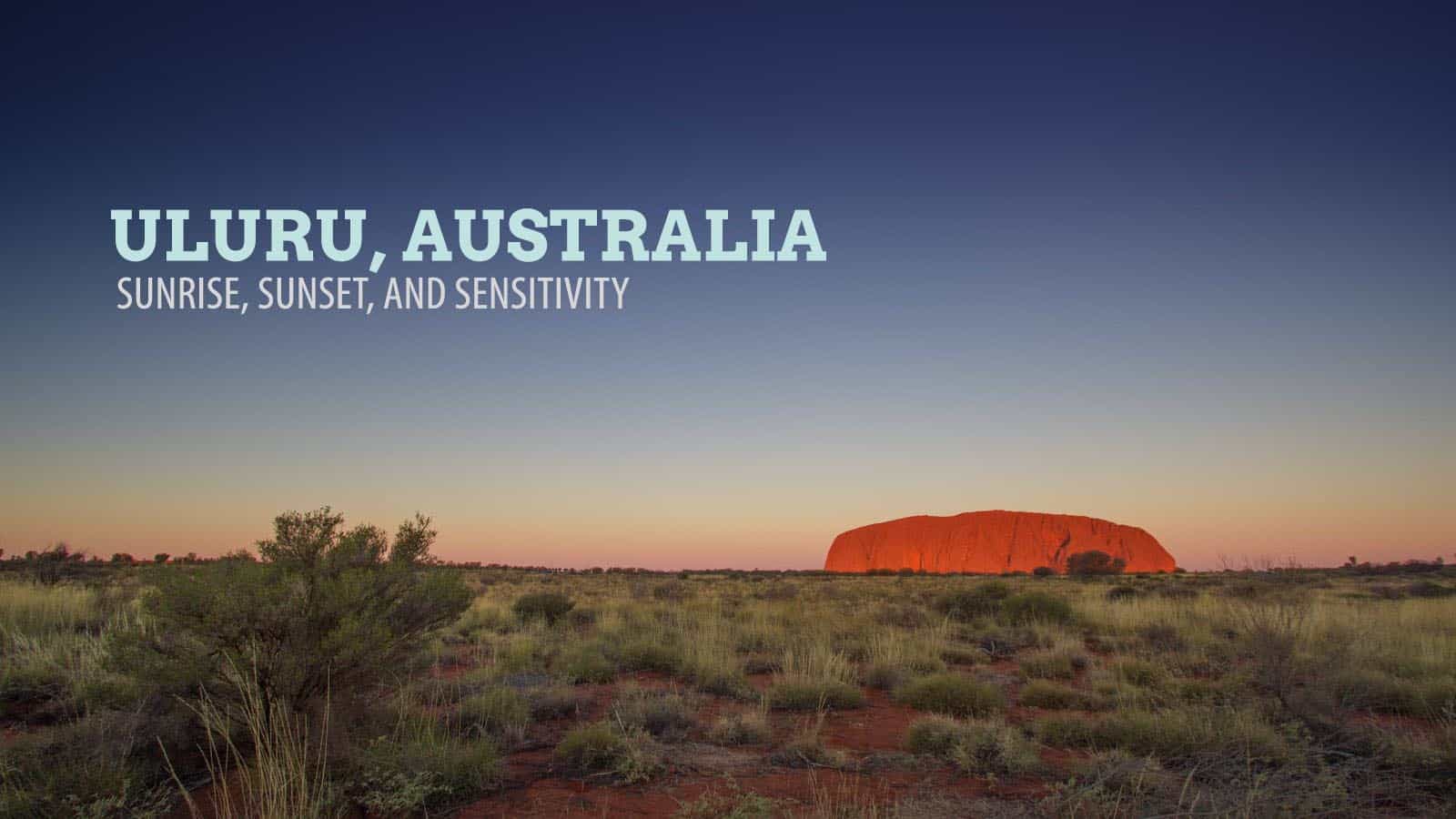

Those tables most likely belonged to a well-off group on a luxury tour. We were not a well-off group, and this was not a luxury tour. All we had were bottles of beer and cider, and a permanent round table. But none of it mattered. There was no room for envy in a heart already filled with awe. Everything was set. We had a good spot, our time-lapse camera was rolling, and the light was beginning to dwindle. Right before us was Australia’s most iconic symbol: Uluru.

“I can’t wait for it to glow.” Our new friend Rachel couldn’t contain her excitement; her eyes glued to the giant rock.

It’s not every day that it does, warned Nick, our ever-reliable-but-sometimes-buzzkill tour guide. Still, everyone hoped that it would that evening. Our shadows painfully, slowly grew longer as the sun started its descent behind us. Venus, Mars, and Jupiter made their appearance as more and more stars showed up almost one by one. The blue skies were no more. The horizon exuded a golden radiance that painted the scene honey and purple.

And then, it glowed.

Our day was made. Our three-day roadtrip from Alice Springs was worth it. I could go home right then and I’d be happy.

But it was great that I didn’t. Apparently, Uluru is much more than just a visual spectacle. Much more compelling is its history, which isn’t always glowing.

What’s in a Rock?

It’s not hard to be captivated by Uluru. Although most famous for its sunset glow, it wears many colors, changing at different times of the day and different times of the year.

It is also one of the only few natural structures sticking out from the flat, flat landscape of Central Australia. It is an “inselberg”, or what my friend Wikipedia defines as “an isolated rock hill or knob that rises abruptly from a gently sloping or virtually level surrounding plain.” The sandstone giant stands 348m tall. But it isn’t its height or aloneness that makes it outstanding. Uluru is a homogenous monolith; “it lacks jointing and parting at bedding surfaces.” It owes its red-brown color to the oxidized iron-carrying minerals. It is — basically — rust.

As if the heart of the continent, Uluru is situated almost at the very center of Australia. The nearest major town is Alice Springs, reachable after a five-hour drive. But there are accommodations and other establishments in a nearby area called Yulara, a common tourist stop.

The next day, we went back to the viewpoint early morning to catch the sun rise from behind the rock. It did not have the signature glow this time, but the sight of its silhouette slowly taking form was just as breathtaking. Despite the biting cold, we stood before the fence and felt our jaws drop to the ground. After a quick breakfast, we drove toward the legendary rock.

Going Up or Going Around?

Many continue to refer to this landmark as Ayer’s Rock, a name given to it in 1873 in honor of Sir Henry Ayers, who was the Chief Secretary of South Australia at the time. But the local Anangu call it Uluru. Today, both names are accepted. But the name is just a manifestation of the site’s controversial past. Over the century, “ownership” and control of Uluru had been a major issue for the Aborigines and the government. It was opened to tourists in 1936. Since the 1940s, it had been promoted as a place to climb, which (among others) upset the local Pitjantjatjara people. For them, Uluru is a sacred site and they have always been forbidden to climb it. On 26 October 1985, the land was returned to the local Aborigines by the government but must be leased to the National Parks and Wildlife Agency. The government and the locals then co-managed it.

Outsiders find it hard to understand the massive cultural significance of Uluru to the Anangu people. Most tourists see a big rock or a hill, something that needs to be conquered. To the native inhabitants of the area, it is their heritage, laws, beliefs, and survival knowledge lumped into a big rock. Uluru is said to have been created during Dreamtime.

The whole concept of Dreamtime is difficult to comprehend; I’m still struggling with it. Called Tjukurrpa in the vernacular, it is the “Aboriginal understanding of the world.” It basically tells how people are connected to the land, animals, and everything else in this world. Part of Tjukurrpa are stories of creation, some of which are set at Uluru. A walk around the base of the hill introduces many of these tales.

When we arrived at the site to begin our tour, Nick (our guide) explained that while climbing is allowed, it is highly discouraged. The sign installed at the start of the trail reads:

“Uluru is sacred in our culture. It is a place of great knowledge.

Under our traditional law, climbing is not permitted.

This is our home….

Please don’t climb.”

The sign, however, encourages visitors to “take a walk around the base and discover a deeper understanding of this place.” There are short walk options but circumnavigating the entire base is highly recommended. Called Uluru Base Walk, it follows a 10-km trail around the rock. We began our casual stroll after sunrise, making brief stops to read what was written on markers, pointing out rock formations and explaining the importance of some parts. In many areas, photography is prohibited. Some spots are still being used in “private rituals” that not all Anangu peole can see. This restriction minimizes the locals accidentally seeing forbidden areas.

Soon after, what I thought was just a casual stroll turned out to be a serious trek, lasting between 3-4 hours. When found ourselves at the point where we started the walk, just near the base of the “climbing trail.” This time, there was already a line, ready to conquer the giant. We sat on the ground and rested while watching people come and go. Many would come close to the massive sign that screamed “Please don’t climb” in multiple languages, read it, and choose to not do it anymore.

Others climbed on.

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park

Lasseter Highway, Uluru NT 0872, Australia

Operating Hours: 8:00 AM – 4:30 PM

Phone: +61 8 8956 1128Rates: AUD 25 per adult (3-day pass)

Entry is free for children under 16.

We visited Uluru as part of a YHA tour package. It comes with 2 nights stay at Alice Springs YHA and a 3-day camping trip to Uluru courtesy of The Rock Tour, which makes a stop at Kings Canyon (Day 1), Kata Tjuta (Day 2) and finally Uluru (Days 2-3).

For more information or to book the tour, visit this site.

Where to stay: Ayer’s Rock YHA Hostel is also known as the Voyages Outback Pioneer Lodge or Outback Pioneer Hotel. They offer air-conditioned and wi-fi equipped rooms at the heart of Yulara Township. There’s a bar, a grill, and a lot of useful facilities on site. There’s also a viewing deck for Uluru sunset within the vicinity.

Book your room here: Ayers Rock YHA Hostel.

We visited Uluru as part of a YHA tour package. It comes with 2 nights stay at Alice Springs YHA and a 3-day camping trip to Uluru courtesy of The Rock Tour, which makes a stop at Kings Canyon (Day 1), Kata Tjuta (Day 2) and finally Uluru (Days 2-3).

We visited Uluru as part of a YHA tour package. It comes with 2 nights stay at Alice Springs YHA and a 3-day camping trip to Uluru courtesy of The Rock Tour, which makes a stop at Kings Canyon (Day 1), Kata Tjuta (Day 2) and finally Uluru (Days 2-3). Where to stay: Ayer’s Rock YHA Hostel is also known as the Voyages Outback Pioneer Lodge or Outback Pioneer Hotel. They offer air-conditioned and wi-fi equipped rooms at the heart of Yulara Township. There’s a bar, a grill, and a lot of useful facilities on site. There’s also a viewing deck for Uluru sunset within the vicinity.

Where to stay: Ayer’s Rock YHA Hostel is also known as the Voyages Outback Pioneer Lodge or Outback Pioneer Hotel. They offer air-conditioned and wi-fi equipped rooms at the heart of Yulara Township. There’s a bar, a grill, and a lot of useful facilities on site. There’s also a viewing deck for Uluru sunset within the vicinity.

Love this post! Brought back great memories of a similar trip I did there :) Happy to have discovered your blog!

Thanks, Lauren! :D

Cool blog and some inspiration for our own trip as a family of four, with two young children – 5 months and 3 years!

We’ve just arrived in Australia and are here for three months. Uluru is on our hit list roughly half way through the trip, so there’s some good bits in here! Thanks

We’ll be covering it on our own blog at https://williamsoztravels.wordpress.com